AN OVERVIEW OF FIRE HAZARD AND VEGETATION CONTROLS IN THE SHIRE OF NILLUMBIK

Submission for

NILLUMBIK RATEPAYERS’ ASSOCIATION to PANEL ENQUIRY into BUSHFIRE PLANNING ISSUES in the SHIRE OF NILLUMBIK

Rod A Incoll, AFSM

Rod A Incoll, AFSM, Grad Dip Bus(Monash), BA (Soc Science), Dip For(Vic), former Chief Fire Officer DNRE, Board Member CFA, Director of AFAC

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Chapter 1 – Introduction

1 Client’s Brief

2 Study Area

3 Methodology

Chapter 2: Bushfire History

1 Introduction

2 Fire impacts 3

3 Observations drawn from past fire experience

4 Summary

Chapter 3: Fire Behaviour

1 Introduction

2 Fire behaviour

3 Bushfire risk in built up areas

4 Managing fire risk

5 Summary

Chapter 4:

Influence of Vegetation Controls

1 Introduction

2 Fire hazard within the study area

3 Fuel management in the study area

4 Sociological perspective

5 Summary

Chapter 5: Conclusions

1 Bushfires – a constant visitor

2 Fuel management is the key to fire safety

3 Locations at risk

4 Vegetation clearance controls

5 Duty of care

Appendix One

1 References

Appendix Two

“Sun News-Pictorial” of 20 Jan 1962

Appendix Three

R.Incoll* – Statement of professional experience in Nillumbik shire and surrounding area.

Appendix Four

Outline of presentation to enquiry

Executive Summary

Concern has been expressed that changes to planning controls over vegetation management in the Shire will increase the fire hazard. These concerns include the mandatory planting of fully structured eucalypt forest required under neighbourhood character guidelines, alterations to the Wildfire Management Overlay, and limitations on roadside clearing of firebreaks.

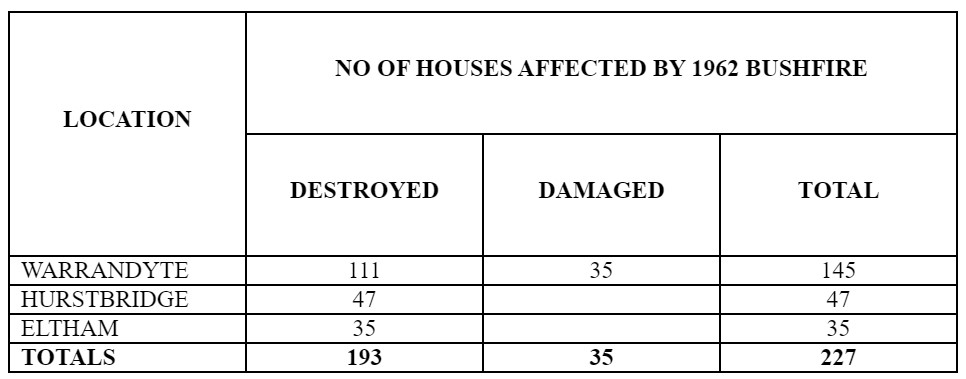

Bushfires have damaged property on many occasions, most notably in 1962 when more than 200 homes were destroyed in Warrandyte, Hurstbridge, and Eltham.

It is inevitable that the region will face damaging bushfires in future, as arson, accident or negligence will result in fires starting during extreme fire danger weather. Fires burning under these conditions cannot be extinguished and will burn and cause damage until the fuel is exhausted or weather conditions change.

Research into past bushfire property loss has provided guidelines for fuel management adjacent to dwellings, so that occupiers have the ability to improve the fire safety of their property with a degree of confidence, for instance by using the CSIRO House Survival Meter – provided such clearance is permitted by the local authority.

This overview has identified that in many locations, the neighbourhood character protocols could be achieved with little or no increase in fire hazard. In other areas, the conditions required for bushfire spread and damage to properties are present. Areas particularly at risk are north facing hill slopes, where forest or grassland meets residential development. Examples are given in the report. Owners have hopefully made an informed choice to live in these areas, with full knowledge of the risks involved; given that Council have a duty of care to ensure overall fire safety.

It is sensible that owners of properties bordering forest, grassland, or Council reserves in these areas have the ability to make their homes bushfire safe. This includes the ability to modify vegetation to meet established fire safety guidelines, with the encouragement and support of Council.

If the ability to do this work is limited by planning controls, then the expressed concerns underlying this report should be noted, and changes made to ensure that those who wish to carry out justifiable fuel management work are able to do so. It is reasonable that fire protection work be authorised under Wildfire Management Overlays, wherever the fire risk warrants this.

The “bottom line” is that restrictions on achieving established standards of fuel management in fire prone areas militate against community fire safety, and may expose the responsible authority to liability for fire loss.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

This chapter deals with the background to the project, and the method used to carry it out.

1 Client’s Brief

The brief received was to investigate and advise on whether changes to planning controls governing vegetation management in the Shire would increase the fire hazard.

These concerns include the mandatory planting of eucalypt forest required under neighbourhood character guidelines, alterations to the Wildfire Management Overlay, and limitations on roadside clearing of firebreaks.

Concern is expressed that planting of eucalypt trees, with ground cover and understory species to form a closed canopy extending from the roadside, was required for residential developments covered by neighbourhood character guidelines, and that the removal of trees for fire prevention reasons was prohibited.

It has been proposed that the Wildfire Management Overlay (WMO) should be removed from specified urban areas. The WMO provisions include the ability to remove ground litter and shrub growth. Concern is expressed that the blanket removal of WMO’s from urban areas such as Hurstbridge will limit the ability of property owners to carry out bona fide fire clearance work.

Roadside firebreaks have been provided for resident and firefighter safety, and the Shire of Nillumbik Fire Protection Plan requires that they be fuel reduced annually. Concern is expressed that this clearance is substantially restricted, as many firebreaks include protected species.

2 Study Area

The study area was defined as the Shire of Nillumbik.

3 Methodology

The methodology used for the study was conference with clients, field observations, literature search, and report writing. In view of the relatively short time frame, the report is necessarily an overview rather than a detailed investigation.

Chapter 2: Bushfire History

1 Introduction

This chapter deals with the fire history of the area, and observations that can be drawn from past bushfire experience. Will severe bushfires that threaten life and property occur in future?

2 Fire impacts

Bushfires causing property loss have occurred since the early days of European settlement. For example, 100 houses were destroyed in the Warrandyte area in mid January 1939, and 2 houses were destroyed in Wattle Glen on 14 January 1944, (Foley, 1947).

In mid January 1962, bushfires swept the area.

Property losses are recorded in Figure 1; see newspaper record, Appendix 2.

Figure 1: HOUSE LOSSES IN 1962 WILDFIRE

Source: Victoria Police statement in “Sun News Pictorial” 20 January 1962

(see Appendix 2)

3 Observations drawn from past fire experience

Extensive research into severe fire events has found that high intensity (property damaging) bushfires have the following characteristics in common:

The more intense and damaging fires occur in summer. Luke and McArthur (1978) indicate that 90% of all bushfire damage in Victoria occurs between mid December and mid March.

- Some fire seasons are more severe than others. These are usually drought years; however there are days almost every summer when damaging bushfires can occur.

- There is an ever-present background level of fire ignition events occurring, including arson, accident, and negligence. When one of these events coincides with extreme fire weather conditions and a dry fuel mass, fires severe enough to threaten life and property will occur.

- Bushfires that cause property damage burn under hot, dry weather conditions, when strong winds are blowing. Such weather is usually, but not always, experienced on declared Total Fire Ban Days.

- While intense wildfires will occur in almost any fire season, there will periodically be years in which severe property damage and even loss of life is experienced. Such years may be decades apart.

While intense wildfires will occur in almost any fire season, there will periodically be years in which severe property damage and/or loss of life is experienced. Such years may be decades apart.

It is inevitable that the Shire will face severe bushfires threatening life and property in years to come.

4 Summary

This chapter pointed out that bushfires have damaged property on many occasions since the area was settled, most notably in 1962 when more than 200 homes were destroyed in Warrandyte, Hurstbridge, and Eltham.

The more intense and damaging fires occur in summer, some fire seasons, usually drought years, are more severe than others. There is an ever-present background level of fire ignition events occurring, including arson, accident, and negligence. When one of these events coincides with extreme fire weather conditions and a dry fuel mass, fires severe enough to threaten life and property will occur.

While intense wildfires will occur in almost any fire season, there will periodically be years in which severe property damage and/or loss of life is experienced. Such years may be decades apart.

It is inevitable that the region will face severe bushfires threatening life and property in years to come.

Chapter 3: Fire Behaviour

1 Introduction

Fortunately, few people have experienced high intensity fire events and cannot imagine what is involved. This chapter provides information on high intensity fire behaviour, to put the bushfire threat in context, and summarises information related to managing fire risk.

2 Fire behaviour

Figure 2: HIGH INTENSITY FIRE

Fire front approaching homes

What is high intensity fire?

The best way to describe a high intensity fire is to liken it a blizzard, to being exposed to a wind so strong that you can barely stand up, so hot you would burn to a crisp, and instead of wind driven snow, a continuous shower of burning bark and leaves hitting you hard. You cannot see or breathe because of acrid wind driven smoke and the noise is fearful. Unless you reach shelter the searing heat will scorch your lungs and peel off your skin, and you will quickly die.

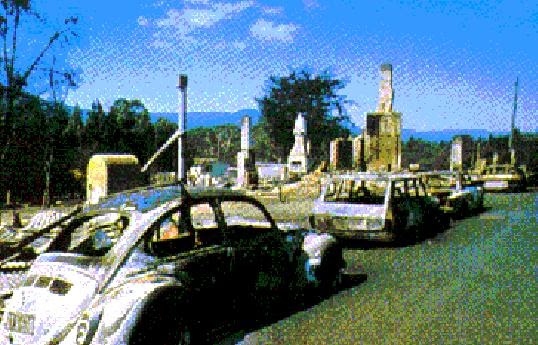

Forests become burnt spars with nothing but white powder underfoot, and homes are reduced to charred and twisted shells. If you have ever come close to experiencing high intensity fire, you will never forget or doubt its awesome power. Fires starting under conditions of high temperature, low humidity and strong winds quickly move from ground fuels through the shrub layer to the tree crowns, and assume unstoppable momentum while fuel and weather conditions persist.

The whole forest structure becomes a roaring, searing, flaming mass, blown forward by the wind at speed. This is known as a “three dimensional” or “crown” fire. The aftermath of the passage of high intensity fire through a small township is shown in Figure 3a.

A major mechanism of fire spread is known as “spotting” in which burning embers are blown ahead of the main front, causing new fires to start. Massive short distance spotting is a major mechanism of fire spread for bushfires. Table 1 shows the spotting distance ahead of crown fires. For instance fires in eucalypt forest fuel loads of 15 t/ha under extreme conditions (FDI of 90) will throw embers 5.4 km ahead of the main fire.

Figure 3: SUMMARY OF FIRE BEHAVIOUR INFORMATION SHOWING

RATE OF SPREAD, FLAME HEIGHT, AND SPOTTING DISTANCE FOR

FIRES IN EUCALYPT FOREST. (McArthur 1967)

Figure 3a: AERIAL VIEW OF THE TOWNSHIP OF MOGGS CREEK AFTER A HIGH INTENSITY FIRE ON 16 FEBRUARY 1983 – REMNANTS OF FIVE HOMES

Can high intensity fires be suppressed?

There is a perception that bushfires can be extinguished and that the effectiveness of modern technology and fire fighting organisation provides a safety net. To explore this idea consider Figure 4.

This shows the fire intensity level at which the main forest fire fighting methods cease to be effective. How does this compare with the fire intensity of typical high intensity forest fires?

FIGURE 4 INTENSITY AT WHICH FIRE

SUPPRESSION IS LIKELY TO FAIL ON A FIRE BURNING IN EUCALYPT FOREST

Figure 5 shows the data in Figure 3 converted to fire intensities. The shaded cells on the lower side of the diagram represent fire intensity levels that are beyond the capability of direct attack on the fire front. Note that in heavy fuels this “suppression threshold” may be exceeded even at moderate fire intensities. This is borne out by data showing property loss and fire intensity on Ash Wednesday at Macedon (Figure 6).

FIRES NOT CONTROLLABLE

Figure 5: SUMMARY OF MCARTHUR’S FIRE BEHAVIOUR INFORMATION IN FIGURE 3, WITH FIRE INTENSITY CALCULATED FOR EACH CELL

3 Bushfire risk in built up areas

security of property

Mt Macedon township up to the 1980’s was a pleasant, leafy retirement haven for the well-to-do, mostly living in large homes with heritage character, on generous allotments. The vast manicured lawns and mainly deciduous and exotic trees were attractions for tourists and boasted the odd “open day” for charity.

No one living there could have imagined the terror and confusion of 16th February 1983 that resulted in the destruction of 239 homes in the township area. Subsequent enquiry into the fires resulted in calls for scientific research and a number of studies were carried out. Wilson (1986) studied the fate of the homes burnt at Mt Macedon, and collected data from each of the house sites with the following results.

Figure 6: FATE OF HOMES ACCORDING TO FIRE INTENSITY CLASS

MT MACEDON, 16 FEBRUARY, 1983

(Wilson and Ferguson 1986)

Figure 7: Aftermath of Macedon fire, 16 Feb 83

(photo: Emergency Management Australia)

Analysis of this data showed that the factors connected with a house surviving a high intensity bushfire included:

· fire intensity (the most important factor), was linked to fuel loading

· slope of the ground downhill of the house site

· house construction, (eg, brick or wooden)

· roof type (eg, tile or shingle), and pitch of roof

· whether house was attended (so spot fires in/on house can be put out)

· whether trees or combustible material (eg, a woodheap) were present near the house.

These factors were mathematically related by analysing the data and were reduced to a formula that enabled a given situation to be evaluated. To make the information more accessible, a dial-up calculator known as the House Survival Meter was developed (Wilson, 1988). This is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8: CSIRO HOUSE SURVIVAL METER

(Australian Government Publishing Service.)

4 Managing fire risk

influence of vegetation controls

The principal factor in determining fire intensity and therefore fire controllability has been shown to be fuel quantity.

As can be seen from Figure 5, fuel has a marked effect on fire behaviour, fire intensity, and therefore fire controllability. In a study based on Melbourne’s meteorological data, Gill, Christian, Moore and Forester (1987) found that bushfires would be uncontrollable on 100 days per year if ignition were to occur when fuel litter weights were 30 tonne/ha. However, if fuel litter weights were reduced to less than 10 t/ha, the potential number of uncontrollable fires would be close to zero. The range of fuel ratings is shown in Figure 10. The rate of forward spread of a fire approximately doubles as fuel quantity doubles, for a given level of fire danger.

This is important, as fuel quantity and arrangement are the only factors affecting fire behaviour that can be manipulated.

influence of topography

Slope and aspect (the direction the terrain is facing) of the terrain greatly influence fire behaviour. The rate of forward spread increases by a factor of two for a 10o slope and by four for a 20o slope. As the forward rate of spread increases, the fire intensity also increases proportionally.

The importance of aspect, and the position of the home on the slope, is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: FIRE SAFETY OF HOMES ON HILL SLOPES VARIES WITH ASPECT

Figure 10: VISUAL ASSESSMENT OF TOTAL FUEL

(after Wilson 1992, 1993)

5 Summary

This chapter provided information on high intensity fire behaviour, and summarised information about managing the fire risk

Fires starting under conditions of high temperature, low humidity and strong winds quickly move from ground fuels through the shrub layer to the tree crowns. Fires burning under these conditions cannot be extinguished, and will burn and cause damage until the fuel runs out or the weather changes.

Wilson (1986) studied the fate of the homes burnt at Mt Macedon, and collected data from each of the house sites. His results showed fire intensity was the key factor in house survival. The factors influencing fire intensity have been summarised in a readily available dial-up calculator known as the House Survival Meter. This easy-to-use tool makes checking the bushfire safety of a home site straightforward.

Slope of terrain and aspect also influence fire intensity; however these are fixed for any given home site.

Fuel quantity has a marked effect on fire intensity, fire behaviour, and therefore fire controllability. If fuel litter weights were reduced to less than 10 t/ha, the potential number of uncontrollable fires would be close to zero. This is important, as fuel quantity and arrangement are the only factors affecting fire behaviour that can be manipulated.

Chapter 4:

Influence of Vegetation Controls

1 Introduction

This chapter deals with the overall fire risk in the Shire, and the influence that changes in vegetation controls could have on the fire hazard.

2 Fire hazard within the study area

The general shape of the landform in the southern part of the Shire is a ridge and spur system rising in the rural area from Yan Yean Reservoir around to Kinglake, and increasing in elevation towards the urban area. This means that the hills and valleys are generally open to the force of the strong north to northwest winds experienced on extreme fire danger days, favouring rapid bushfire development. Many of the hill slopes are in the range of 20o to 30o. This increases the rate of fire spread by a factor of two to four times (p.9).

There are significant areas of eucalypt forest of yellow box, red box and peppermint remaining on the northern and north western aspects of many of the steeper slopes, with messmate stringybark and peppermint on the southern aspects and manna gum in the gullies.

Figure 11: TIMBERED HILL SLOPES FACING NORTH WEST

The canopy height of the trees on the north and northwestern aspects is generally less than 10 metres, (see Figures 13 and 14), a factor which enhances rapid crown fire development on steep exposed slopes. While much understory has been cleared for settlement or grazing on hill slopes, there are hill top reserves such as Temple Ridge and Bailey Gully Reserve near Hurstbridge, with a full understory of ti-tree at very high to extreme fuel levels in some gullies (Figure 13).

Figure 12: TEMPLE RIDGE RESERVE 185 J11

Figure 13: TEMPLE RIDGE RESERVE 185 J11

Figure 14: TEMPLE RIDGE RESERVE 185 J11

The residual native forest on the exposed slopes of many ridges facilitates wildfire development under extreme conditions, by ignition from embers up to five kilometers distant (see Figure 3). So fire pathways are available from rural land into settled areas, through the remnants of native vegetation and the network of parks and reserves. However the fact that topography and vegetation favour fire development has not changed since the 1962 fires.

what has changed since the 1962 fires?

The most obvious change since the 1962 fires is the population increase in the Shire, with extensive building in estates on allotments of generally less than 1000 square metres in township areas. Rural residential living has also become much more in vogue. Homes have replaced understory vegetation on many hill slopes.

There have been marked Improvements to road access on main routes since the 1962 fires. However the access to properties on steep hillsides is often narrow and winding, and scope for road improvement is limited by the topography. This makes exiting of residents and access by fire crews in a fire situation hazardous. Resident and firefighter fatalities have occurred under similar conditions in the past. Public policy encouraging fire planning by families including early withdrawal to safe areas, and declaration of “no go” areas for fire crews, have been much more widely implemented as a result.

3 Fuel management in the study area

The conditions required for bushfire spread and damage to properties are present in many locations.

North and northwest facing hill slopes, where the forest or grassland border meets rural residential or residential development, are particularly at risk. These locations are described as the “rural-urban interface” or the “forest-urban interface”. Fire experience has shown that this interface is where the greatest potential for bushfire loss and damage lies.

The landscape and vegetation described may be fire prone; however it is this very character that has attracted a growing population to the area. Residents have hopefully made an informed choice to live in these areas, with full knowledge of the bushfire risks involved.

Council’s duty of care to support and educate the community and ensure overall fire safety is reflected in the Municipal Fire Protection Plan. The requirement for this plan stems from the Country Fire Authority Act. Implementation of fire protection provisions in a fire prone municipality is complex, owing to the balance required between aesthetics, environmental conservation, and fire safety.

neighbourhood character guidelines

Concern has been expressed that the planting of eucalypt trees, with ground cover and understory species to form a closed canopy extending from the roadside into the allotment and close to the dwelling, is to be required for residential developments covered by neighbourhood character guidelines.

The guidelines militate against the removal of trees and understory vegetation, and require the planting of forest trees, understory species and ground cover on residential allotments from the street front, so as to allow the home “to appear to be within the tree canopy”. “Threats to preferred future character” include “removal of vegetation including trees forming a strong canopy”. The caveat that this should be done “where compatible with other planning requirements including bushfire safety” is stated on the precinct guidelines.

The CFA Community Safety response on the neighbourhood character study has noted that residents should be allowed to clear up to 30 metres from their home without the need for a planning permit. The “House Survival Meter” confirms this. The planning provisions need to make this clear, to ensure fire safety in appropriate areas.

This overview has identified that in many locations, the neighbourhood character protocols could be achieved with little or no increase in fire risk. In other areas, the conditions required for bushfire spread and damage to properties are present. Areas at risk are north facing hill slopes, where forest or grassland meets residential development.

Dwellings in locations 4,5 or 6 in Figure 9 would be unduly exposed to fire risk if adequate vegetation clearance was not maintained in interface areas.

In view of the distance of spotting associated with extreme fire events (see Figure 3), houses in locations well within urban boundaries could be placed at risk, especially if homes were unattended. A typical location that could be at risk under these circumstances is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15: NORTH FACING LINEAR RESERVE

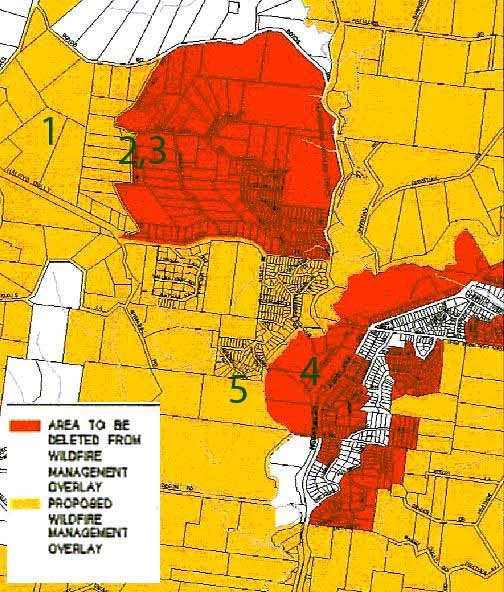

Wildfire Management Overlay

The Wildfire Management Overlay (WMO) is an important mechanism for identifying fire prone locations and allowing fire clearance work without the need for a planning permit.

This is important because fuel quantity and arrangement are the only factors affecting fire behaviour that can be manipulated (page 9).

Concern is expressed that the removal of the WMO from urban areas will limit the ability of property owners to carry out bona fide fire clearance, as a planning permit would then need to be obtained for this work. In view of the importance of the WMO in fuel management, modification of the overlay needs to be based on a careful and detailed appraisal of the fire risk.

Modification of Wildfire Management Overlay

Figure 16 shows portion of the WMO scheduled for removal at Hurstbridge. Should this removal proceed, and the WMO be removed, two changes will be evident. Firstly, residents would be required to obtain written permission to remove vegetation, including clearance around dwelling for fire protection purposes. Secondly, the neighbourhood character requirement will see an increase in forest tree and shrub plantings in proximity to buildings within these areas.

Figure 16: WILDFIRE MANAGEMENT AMENDMENT C11

(part of map shown)

A survey covering items listed below was made along the main routes through the areas coloured red, that is, areas where removal of the WMO is proposed.

- fuel loading – vegetation within 30 metres of main structure.

- slope of the home site

- aspect – major direction slope faces

- likely radiant heat load on house

- nature of access roads

Photographs of randomly selected home sites have been included as figures 17 – 20. The fuel loading within 30 metres of most residences was clearly in excess of the house survival guidelines. Many homes were located on a slope steep enough to accelerate the rate of spread of a bushfire, and also faced a north to west exposure.

The radiant heat load from a crown fire on many houses in this area would imperil the structure and persons sheltering within. The access roads are generally narrow and winding and not conducive to safety of persons attempting to flee a fire, or fire crews seeking to assist them.

Many of these homes require vegetation modification and a range of other measures in order to achieve fire safety. Hopefully, the residents are fully informed about fire safety and have made a conscious decision to live under their present circumstances.

The removal of the WMO from areas close to the rural-urban interface would make the level of vegetation modification required for fire safety difficult to achieve, to the detriment of a resident who wished to comply with accepted fire safety guidelines.

Figure 17: House 1

Figure 18: Houses 2 and 3

Figure 19: House 4

Figure 20: House 5

roadside firebreak clearance

Roadside firebreaks have been provided for resident and firefighter safety, and would normally be fuel reduced annually.

Concern is expressed that the annual clearance of strategic roadside firebreaks has been substantially restricted, as clearance of protected species is prohibited.

Roadside firebreaks are an integral part of the Municipal Fire Prevention Plan and any limitation on effective clearance needs to be carefully validated against the objectives set for community protection under the this Plan.

4 Sociological perspective

Major bushfires have a traumatic impact on individuals and the community, to the extent that a turnover property and residents takes place after an extreme fire event. Fire protection lessons are re-learned, and community interest in fire safety rises to new heights.

After the 1962 fires, the Lower Yarra Group of fire brigades established a headquarters at Kangaroo Ground, with a fire co-ordination centre and updated communications. Strong community support ensured that an airstrip was established nearby. Three Cessna aircraft were purchased with private funding for fire surveillance on fire danger days. However homes were rebuilt, and the natural forest regenerated. Fires of this intensity are infrequent, sometimes decades apart, and general public awareness of the 1962 fire impacts within the community have all but faded away.

As time passes, generations of people without bushfire experience either become confident that serious damaging bushfires will never recur, or have no perception of the fire risk that is present in their locality. In time, comfortable complacency replaces fire awareness across the community.

This emphasises the point already made that implementation of fire protection provisions in a fire prone municipality is complex, owing to the balance required between aesthetics, environmental conservation, and fire safety.

5 Summary

This chapter dealt with the overall fire risk in the Shire, and the influence that changes in vegetation controls could have on the fire hazard.

The conditions required for bushfire spread and damage to properties are present in many locations. Those particularly at risk are north facing hill slopes, where forest or grassland border meets rural residential or residential development. This is described as the “rural-urban interface” or the “forest-urban interface”. Fire experience has shown that this interface is where greatest potential for bushfire loss and damage lies. Residents have hopefully made an informed choice to live in these areas, with full knowledge of the bushfire risks involved.

This overview has identified that in many locations in built-up suburban areas, the neighbourhood character protocols could be achieved with little or no increase in fire hazard. In others, particularly the rural-urban interface, the conditions required for bushfire spread and damage to properties are present .

The CFA Community Safety response on the neighbourhood character study has noted that residents should be allowed to clear up to 30 metres from their home without the need for a planning permit. The “House Survival Meter” confirms this parameter. The implementation of the protocols needs to make this clear to ensure fire safety in fire prone locations.

Concern is expressed that the removal of the Wildfire Management Overlay from urban areas will limit the ability of property owners to carry out bona fide fire clearance, as a planning permit would then need to be obtained for this work. In view of the importance of the WMO in fuel management, modification of the overlay needs to be based on a careful and detailed appraisal of the fire risk.

Concern is expressed that the annual clearance of strategic roadside firebreaks has been substantially restricted, as clearance of protected species is prohibited. Roadside firebreaks have been provided for resident and firefighter safety, and would normally be fuel reduced annually. Firebreaks are an integral part of the Municipal Fire Prevention Plan, and any limitation on effective clearance needs to be carefully validated against the objectives set for community protection under the this Plan.

As time passes, generations of people without bushfire experience either become confident that serious damaging bushfires will never recur, or have no perception of the fire risk that is present in their locality. In time, comfortable complacency replaces fire awareness across the community.

This adds emphasis to the point that implementation of fire protection provisions in a fire prone municipality is complex, owing to the balance required between aesthetics, environmental conservation, and fire safety. Nevertheless, there is a duty on the part of responsible authority to place fire safety before other considerations in identified fire prone areas.

Chapter 5: Conclusions

1 Bushfires – a constant visitor

Bushfires have damaged property on many occasions since the Shire was settled, most notably in 1962 when more than 200 homes were destroyed in Warrandyte, Hurstbridge, and Eltham.

Fires starting under conditions of high temperature, low humidity and strong winds quickly move from ground fuels through the shrub layer to the tree crowns. Fires burning under these conditions cannot be extinguished, and will burn and cause damage until the fuel is exhausted or the weather changes.

While intense wildfires will occur in almost any fire season, there will periodically be years in which severe property damage and/or loss of life is experienced. Such years may be decades apart. It is inevitable that the Shire will face severe bushfires threatening life and property in years to come.

2 Fuel management is the key to fire safety

Fires starting under conditions of high temperature, low humidity and strong winds quickly move from ground fuels through the shrub layer to the tree crowns. Fires burning under these conditions cannot be extinguished, and will burn and cause damage until the fuel is exhausted or the weather changes.

“Ash Wednesday” fire losses have been researched and the factors influencing fire intensity were summarised in a readily available dial-up calculator. So residents (and those responsible for implementing fire regulations) are able to draw on the lessons of past bushfire loss and damage by using the House Survival Meter to check the bushfire safety of home sites.

Fuel quantity has a marked effect on fire intensity, fire behaviour, and therefore fire controllability. If fuel litter weights were reduced to less than 10 t/ha, the potential number of uncontrollable fires would be close to zero. This is important, as fuel quantity and arrangement are the only factors affecting fire behaviour that can be manipulated.

3 Locations at risk

The conditions required for bushfire spread and damage to properties are present in many locations in the Shire. Those particularly at risk are north facing hill slopes, where forest or grassland border meets rural residential or residential development. This is described as the “rural-urban interface” or the “forest-urban interface”.

Fire experience has shown that this interface is where greatest potential for bushfire loss and damage lies. Residents have hopefully made an informed choice to live in these areas, with full knowledge of the bushfire risk involved.

4 Vegetation clearance controls

This overview has identified that in many mainly built up suburban locations, the neighbourhood character protocols could be achieved with little or no increase in fire hazard. In others, the conditions required for bushfire spread and damage to properties are present.

The CFA Community Safety response on the neighbourhood character study has noted that residents should be allowed to clear up to 30 metres from their home without the need for a planning permit. The implementation of the protocols needs to make this clear to ensure fire safety in fire prone locations.

Concern is expressed that the removal of the Wildfire Management Overlay (WMO) from urban areas will limit the ability of property owners to carry out bona fide fire clearance, as a planning permit would then need to be obtained for this work. In view of the importance of the WMO in fuel management, modification of the overlay needs to be based on a careful and detailed appraisal of the fire risk.

Concern is expressed that the annual clearance of strategic roadside firebreaks has been substantially restricted, as clearance of protected species is prohibited. Roadside firebreaks would normally be fuel reduced annually. Firebreaks are an integral part of the Municipal Fire Prevention Plan, and any limitation on effective clearance needs to be carefully validated against the objectives set for community protection under the this Plan.

5 Duty of care

As time passes, generations of people without bushfire experience either become confident that serious damaging bushfires will never recur, or have no perception of the fire risk that is present in their locality. In time, comfortable complacency replaces fire awareness across the community.

This adds emphasis to the point that implementation of fire protection provisions in a fire prone municipality is complex, owing to the balance required between aesthetics, environmental conservation, and fire safety. Nevertheless, there is a clear public duty on the part of responsible authority to fully address fire safety ahead of other considerations in identified fire prone areas.

In this respect, it may be appropriate for the local authority to seek advice as to whether refusal to allow vegetation removal to comply with research-based criteria, or failure to actively inform persons living in a fire prone area of the hazard, could give rise to liability for fire loss.

Appendix One

1 References

Foley J C (1947) A study of meteorological conditions associated with bush and grass fires and fire protection strategy in Australia, Bulletin No 38, Bureau of Meteorology, 234pp.

Gill A M, Christian K R, Moore P H R and Forester R I (1987) Bushfire incidence, fire hazard, and fuel reduction burning, in Australian Journal of Ecology 12 299-306.

Gill A M (1975) Fire and the Australian Flora, A Review in Australian Forestry Vol 38 21pp.

Luke R H and McArthur A G (1978) Bushfires in Australia Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra 359pp.

McArthur A G (1967) Fire Behaviour in Eucalypt Forests Leaflet 107 Forestry and Timber Bureau 36pp

Wilson A A G (1992) Eucalypt Bark Hazard Guide Research Report No 32, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, 16pp.

Wilson A A G (1993) Elevated Fuel Guide Research Report No 35, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, 22pp.

Wilson A A G (1988) A simple device for calculating the probability of a house surviving a bushfire in Australian Forestry 51 (2) 119-123

Wilson A A G and Ferguson I S (1986) Predicting the probability of house survival during bushfires in Journal of Environmental Management 23 259-270

Appendix Two

“Sun News-Pictorial” of 20 Jan 1962

Appendix Three

R.Incoll* – Statement of professional experience in Nillumbik shire and surrounding area.

- was Forests Commission District Forester Toolangi 1976 – 1984, area of responsibility included all of the Shire of Nillumbik, country north to Yea and Whittlesea, and west to the MFB catchment boundary.

- fire responsibilities included Kinglake National park and all public land to Whittlesea.

- extensively travelled through the shire area and surrounds in the course of work;

- attended CFA fire brigade and group meetings throughout the area;

- was departmental representative on Municipal fire prevention committee, which met at Lower Yarra group headquarters monthly to discuss fire hazards and coordination activities. Duties included coordination between departmental fire prevention plan and the fire brigade plans; brigades invited to participate in fuel reduction burning operations.

- was involved in combating many fire outbreaks during this period including large wildfires in Kinglake national park, Mt Robertson state forest, Flowerdale area, and Mt Disappointment state forest during this period.

- visits for the Nillumbik Ratepayers’ Association study were to update knowledge and undertake specific enquiry, and are not the extent of R Incoll’s experience in this locality.

Rod A Incoll, AFSM, Grad Dip Bus(Monash), BA (Soc Science), Dip For(Vic),

former Chief Fire Officer DNRE, Board Member CFA, Director of AFAC

Appendix Four

Outline of presentation to enquiry

· Introduction

· Experience in area – (Appendix 2)

· Importance of fuel management

· case study – Macedon

· fuels and level of fire safety observed in area

· conclusion